|

What if Godzilla was a projection of your issues? That's the question posed by "Colossal," a new film by Nacho Vigalondo in which an alcoholic screwup named Gloria (Anne Hathaway) unleashes terror on Seoul, South Korea, in the form of a giant monster by getting blackout-drunk.

This sounds like the premise of a "Saturday Night Live" sketch blown up to feature length, but part of the weird charm of "Colossal" is its willingness to be that kind of movie to the Nth degree. It warmly embraces the central idea and explores it in detail, without burdening it with gravity that it can't support. Vigalondo, who has carved out a niche making wry, small-scaled, rather peculiar genre films, doesn't do that. This movie feels as if somebody woke from an intense nightmare, decoded it and realized it was rather unsubtly working through some of their unresolved problems, then brought it to Judd Apatow and said, "Here's your next comedy." Read more

0 Comments

In theory, "Rules Don't Apply" is about a couple of young people--Alden Ehrenreich, a driver for Hughes, and a would-be starlet played by Lily Collins, who moves out to Los Angeles with her mother, who's played by multiple Oscar nominee Annette Bening, Beatty's wife. Collins' character is one of 28 young women being groomed as starlets by Warren Beatty's Howard Hughes, theoretically for a movie that he hopes to direct. There are talent classes; lavish parties and shots of vintage architecture; cars and clothing; a budding romance between the two young leads; and a sharp right turn into an age-inappropriate relationship between the heroine and Hughes, who is defined throughout the film's first third mainly as a disembodied voice on the telephone, like the way "Seinfeld' treated George Steinbrenner on "Seinfeld" and the comic strip "Doonesbury" depicted presidents.

But as Scout Tafoya's latest edition of "The Unloved," and one of my favorites, points out, "Rules Don't Apply" is mainly about the mystery and audacity of its writer, director and co-star, Warren Beatty, a man who's nearly as curious a figure as Howard Hughes. It makes sense that Beatty would have made his long-delayed return to filmmaking and acting with "Rules Don't Apply," playing the reclusive aviation magnate turned film producer. Read More Confusion and Carnage: An Interview With Film Critic Adam Nayman About The Films Of Ben Wheatley3/26/2017 Critic Adam Nayman knows how to start an argument. The Toronto-based writer, whose work has appeared in such journals as Cinema Scope, Slant and AV Club, made a stir in film critic circles a few years back with his book "It Doesn't Suck," which argued that Paul Verhoeven's widely reviled "Showgirls" was, in fact, rather interesting, and in some ways marvelous. His new book about writer/director Ben Wheatley, titled "Ben Wheatley: Confusion and Carnage," treats its titular subject, who is barely known outside of art houses, as an artist who's on the cusp of greatness. I talked with Nayman about his book, which is in stores now and can be ordered here.

Why write a book about Ben Wheatley at this point in his career? There's something very exciting about trying to write a book about a director before he or she has reached the finish line, and it seemed to me like Ben Wheatley was a filmmaker who could be interesting from two angles at once. On the one hand, he's done some very distinctive, substantial work in a very short period of time. On the other, he's possibly on the verge of moving on to bigger and more elaborate projects. So there's something open and provisional about taking stock less than a decade in. Read More Loud, trashy, sweet and weird, the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers reboot “Power Rangers” is not merely an ideal film for rambunctious and undemanding 12-year olds, it actually sees the world through their eyes.

In theory, the heroes are high school students. But they’re actually a Disney Channel-styled fantasy of the splendors that await kids when they finally become full-fledged teenagers and can Do Whatever They Want. These heroes are misfits. They gather in detention in their high school, a scenario that promises to turn into “The Mighty Morphin Breakfast Club Rangers.” Lo and behold, that’s what you get: a mix of shenanigans, heart-to-heart talks and widescreen punch-outs between monster battles. Read More There was grumbling back in 1994 when “The Fugitive” got an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. It was a fiercely competitive year—the film's rivals included “In the Name of the Father,” “Remains of the Day,” “The Piano” and the ultimate winner, “Schindler’s List”—and it was widely assumed that “The Fugitive” had been been granted the token “popular” Best Picture slot as a sop to regular folks who preferred escapism to heavy historical drama. It was a thriller based on a beloved but not particularly deep TV series, it starred action-adventure king Harrison Ford, and it wasn’t making statements about anything.

I watched "The Fugitive' again last night for the first time in years and it didn’t seem like the weak link at all. It's as finely crafted an example of its specific subgenre—“wronged man tries to clear his name”—as you’re going to find. It’s as much sheer fun as “Casablanca,” “All About Eve,” “The Sting,” “Annie Hall” and “Rocky,” all of which won Best Picture over more superficially “serious” competition by embodying excellence without seeming to flaunt it. It glides across the screen like a falcon waiting for the right moment to dive. Read more I'm in the tank for Terrence Malick. I don't believe that the Austin-based director has ever made a bad movie, just ones that were too fragmented, mysterious and intuitive to connect with a wide audience. I thought "Knight of Cups" was one of last year’s most daring features, but I realize this is a minority opinion. Mention the director to a movie buff these days and you’re likely to get jokes about voice-overs and perfume ads and twirling in fields, plus complaints that Malick is too much of this and not enough of that, and not what he used to be.

I don't care. I love that after 44 years of feature filmmaking, his style is still an issue. Even at its most obtuse, Malick’s work never plays by commercial cinema's rules, coming at characterization and story from odd angles when it isn’t chasing the ineffable, as his camera chased a butterfly in “The Tree of Life.” The actor and filmmaker Tim Blake Nelson, who had a small role in Malick's epic 1998 war poem "The Thin Red Line," said the difference between Malick and most other filmmakers is "the difference between [Georges] Seurat painting with dots and [Paul] Cezanne, who's a more painterly painter." Read more The American college fraternity experience has birthed a growing subgenre of films, with Richard Linklater's "Everybody Wants Some!" and Andrew Neel's "Goat" sparking recent discussion for the way they use Greek organizations' obsession with male bonding rituals and tradition as a way to criticize the world beyond college. The tale of an "Everyman" college student being drafted into a fraternity as a pledge and sticking with it through Hell Week and beyond is inherently dramatic, and not just because it comes with a handy built-in time frame, one semester or year of higher education. Almost every pledge story told on film seems to end up becoming the story of innocence lost or ignorance reinforced. The young man seeking fraternity initiation goes into the experience in search of abstract ideas like "brotherhood" and "oneness," and emerges on the other side cynical and disillusioned or radicalized and awake. The journey can be played at any emotional pitch, and because the main characters are young men living in the zone between adolescence and true adulthood, the filmmaker can play it all sorts of ways, from slapstick comedy ("Old School") to horror ("The Brotherhood")

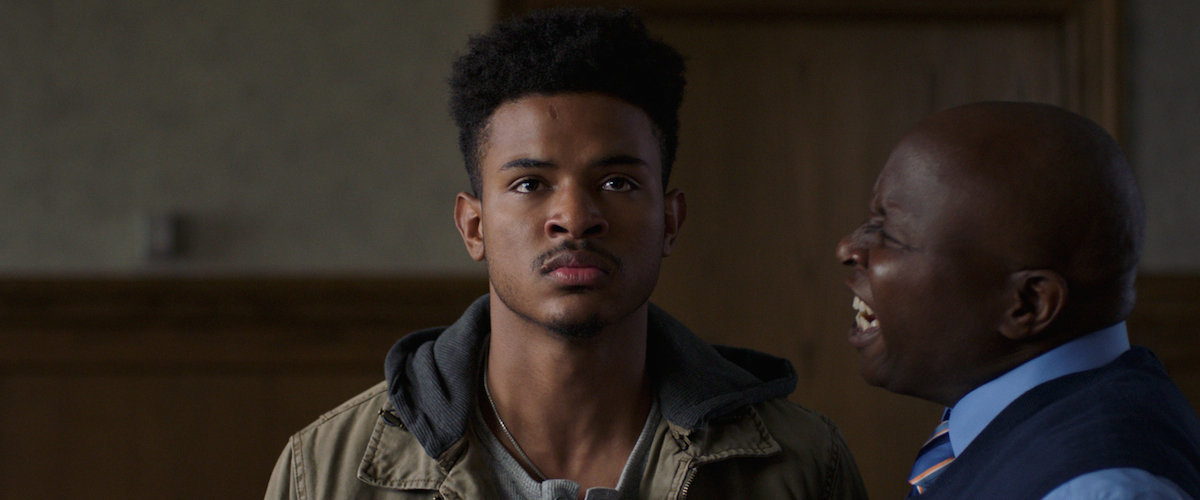

"Burning Sands," Gerald McMurray's feature filmmaking debut, is one of the fresher entries, thanks mainly to its setting: a historically black fraternity on a historically black campus like Howard, the university where the co-writer and director got his degree. Spike Lee's second feature "School Daze" had a subplot set in a black frat and showcased a lot of hazing, but the scenes were played mainly for very grim laughs. "Sands" presents itself in trailers as a comedy along those lines, but it's no joke. McMurray's strongest virtue is his ability to thread that comedy-drama needle while he tells the story of Zurich (Trevor Jackson), aka Z, into Lambda Phi, a prestigious Greek organization once attended by the school's dean (Steve Harris), who proposes the young man for membership. Read More All monster films fall into one of two categories: the kind that takes its time revealing the monster, and the kind that shows you the monster right away and never leaves it for long. Think “Jaws” (fins and scary music for the first hour) as opposed to “Deep Blue Sea” or “Sharknado” (Shark-o-Rama pretty much throughout). Most versions of the King Kong story have fallen into the first category: the 1933 original, the 1976 remake, and Peter Jackson’s three-hour 2005 version unveiled the big ape gradually. “Kong: Skull Island,” on the other hand, introduces Kong after less than half an hour, then keeps him (and lots of other big, scary creatures) front and center throughout the film’s 118-minute running time. There’s even a moment where another character tells a story about Kong battling creatures and the movie cuts to images of Kong battling the creatures, in case you weren’t getting your fill of monster-on-monster action.

I’m not mentioning the difference in approach to condemn the new Kong: quite the contrary. This one—about a team of soldiers and scientists that gets stranded on Skull Island during a mission to map the island’s geological interior with explosive charges, which you absolutely should not do when visiting a place called Skull Island—is a half-magnificent, half-misguided example of a “show me the monster” movie. At its best it reminded me of “The Mysterious Island” and “The Land that Time Forgot,” films that were little more than collections of monster-driven action scenes hitched to a perfunctory story about explorers wandering a jungle, doing stuff they were warned not to do, and getting eaten. Read more My grandfather lived eighteen months after my grandmother died of bone cancer. He spent the last 18 months of his life wasting away in the Retirement Inn in Dallas, Texas. My mother used to drop me off there to spend the day with him every Saturday and sometimes on Sunday. I was a sophomore in high school. I don't know if my mother really understood how bad things were getting or how much care he required. I used to help him take a shower. First I'd help him take his clothes off, then I'd walk him to the shower, then I'd stand there while he stood under the water, and then finally I'd help him towel off. He needed help with all this because he'd had a stroke and couldn't really lift his arms above his shoulders. I helped him to to the bathroom, too. Sometimes if he was really tired or was having issues with his arms, I'd wipe him.

I don't remember when, exactly, that the dementia hit him. But it got steadily worse during his last six months. Sometimes he couldn't remember my name. Other times he'd call me Jake, which was the name of one of his brothers. And there were a few times when I knew that he had totally forgotten who I was, and was pretending he remembered because he didn't want to be rude. Grandpa was a gentleman that way. Read more "Table 19" is a movie for everyone who has ever felt deeply uncomfortable at another person's wedding reception. That might not sound like a ringing endorsement—in fact it would make one of the least appetizing DVD box quotes of all time—but there is such a thing as a under-served market, and this movie serves it. Maybe too well, as we'll see.

The title refers to the number of a table at a wedding reception. It's far away from the bride's and groom's family tables. In fact it's about as far back as you can get and not be out on the street. It takes a while for everyone at the table to figure out the common element that resulted in all of them being placed at this particular table. Suffice to say that they all have a problematic relationship with somebody in the wedding party, and that's how they ended up seated in a corner near a restroom. Read more |

Matt Zoller SeitzFilm critic and filmmaker. Archives

April 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed